“I, Ennio Morricone, am dead,” wrote the composer before bidding farewell. His music, on the other hand, cannot. And so it is that creators and artists always leave us without leaving us, and so it is that memory ensures that they are kept alive, kept safe.

Notte Morricone is my gift, a devout tribute to the beauty he gave to the world. Ennio Morricone could be my father, or my grandfather, I am a direct heir to his legacy, of the films that (masterpieces, good, mediocre, or bad) owe him an immeasurable debt.

Before delving into his music, the whistling of his tunes was already a recurring sound in my life. I am the son of parents who grew up with his Once Upon a Time in America, and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. I, among many other things, grew up with his melodies playing in the living room of my home. He may not have known it, but his music was not only the music for those films, it was also the soundtrack of our childhood. Ennio put his creativity, his inspiration, his heterodoxy at the service of the “dream factory”, embedding those sounds in our memory, becoming a classic, the embodiment of the intellectual composer, the popular musician, almost a rock star. And it is in that generous act of creating and sharing beauty with us that my imagined world of Morricone begins to take shape. It is not just about working with his music, much less explaining it, since he has already said everything there is to say; it is about composing a new melody that runs parallel to the presence of his music in our lives.

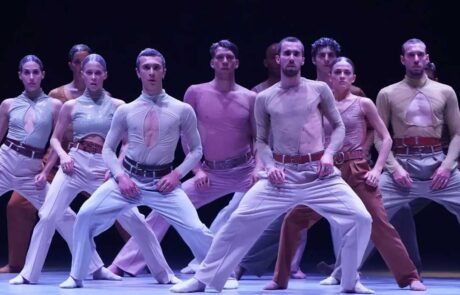

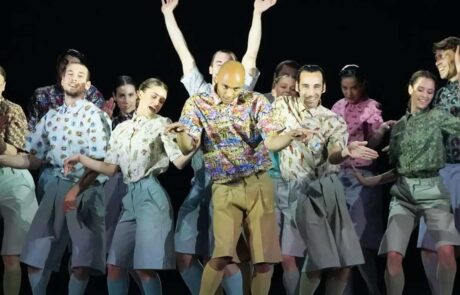

Notte Morricone unfolds in the twilight of an ordinary night in the life of a creator, who — alone and dazed in front of his sheets — takes notes and visualizes melodies for films that do not yet exist, bringing stories back to life in the rarefied air of his room.

The night will be full of visitors, some musicians, who will respond to his creative call to record his fleeting ideas in a makeshift recording studio. And there, among the sheets and musical notes, a boy will appear, the one who wanted to be a doctor, the tireless chess player, the one who knew he would never play the trumpet like Chet Baker because fate had reserved a better place just for him, a place that would make him an icon for all eternity. And the night will continue to advance, turning his home in a recording studio, in the duality of his free mind and his mind that is creating music for films that would become the music of a century, turning his home into a cinema, where visitors of all kinds will come to watch his films and spend the night with him.

And every night will be a new opportunity to bring the dreams of all the musicians, the children, the lovers and lone cinema-goers to life.

Morricone’s music gave sound the things that are left unsaid, those that remain inside. Disassociating his music from the films is a complex and almost suicidal job, but I know that today he would be very happy to know that his music could be emancipated from the cinema and live tonight in a theater.»

Marcos Morau

Director and choreographer