The first performance of the ballet Pulcinella was at the Paris Opera in 1920, by Djagilev’s Ballets Russes; the music, by Igor Stravinskij, was inspired by pages by G. B. Pergolesi and other authors of the 17th and 18th centuries. The composer gives his own sign to the dancing pages in themselves, like so much music of the 18th century: in tune with the subject, he makes a gentle caricature of it, celebrated for the richness of its rhythms and the freshness of its harmonies, exalted by Leonide Massine, choreographer, and Pablo Picasso, for his scenes and costumes.

In creating his own version, Michele Merola respects the past, and the great masterpieces produced on the subject, but moves on his own path. The soundtrack is composed of some pieces of the ballet and the “excursions” made by the composer Stefano Corrias. The contamination of the original score is dictated by the need to have more intimate moments, more bare from the musical point of view, to be able to clarify who is really Pulcinella: the choreographer wanted to highlight in this work the solitary, melancholy and dramatic side of the Neapolitan standard bearer.

“Pulcinella – says the choreographer – is a person, is an image, is a thought of loneliness. It is a thought that never dies, in fact in choreography this character seems to die several times, but then always rises, a sign of his continuous possibility of rebirth, because the freedom that Punchinello carries within him, all that is new, all that is freedom, all that is truth could be suffocated, but always comes back to life.”

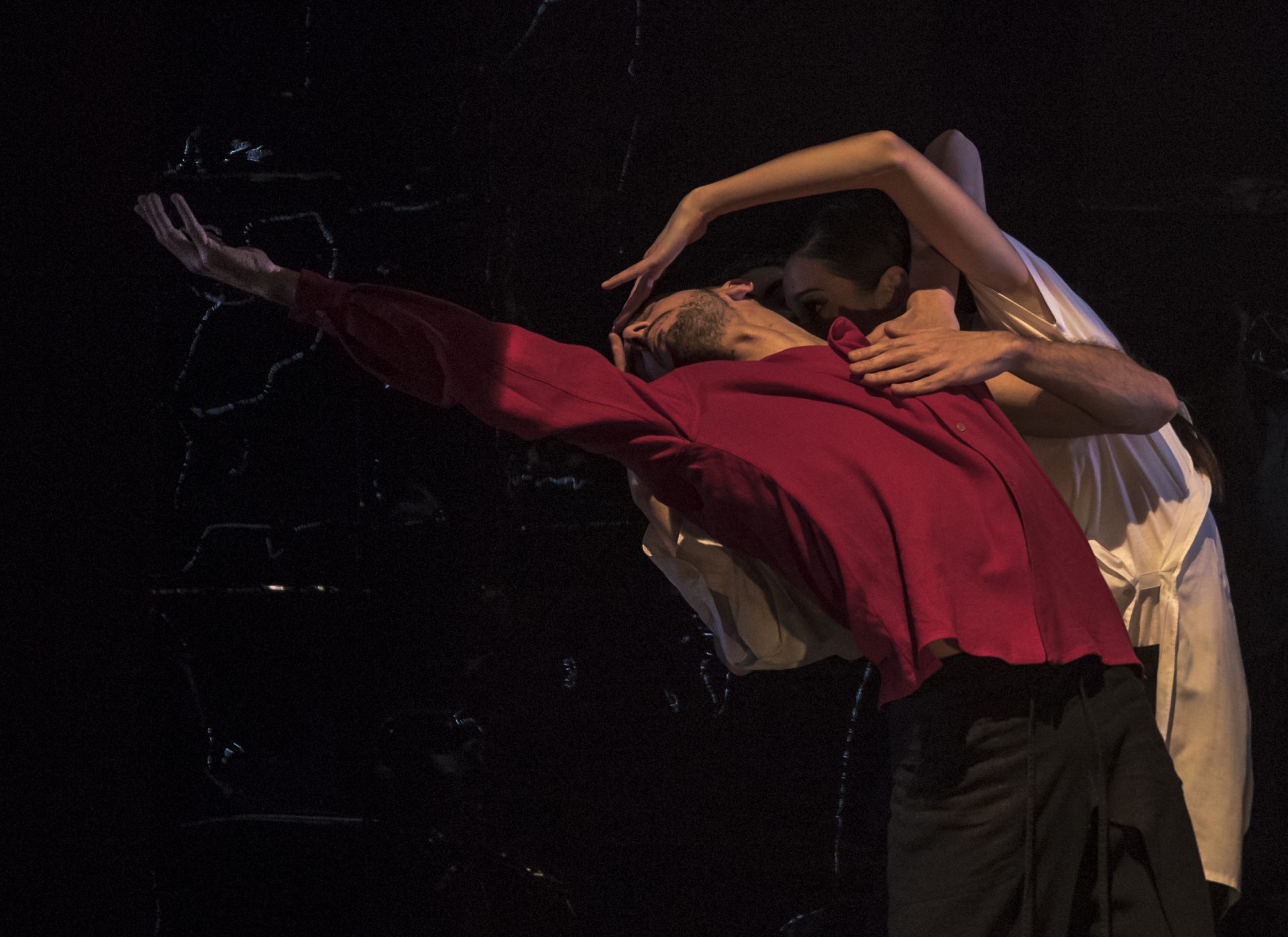

In the predominant black and white of the costumes and the scene, only a hint of red appears: it is Pulcinella, whose heart beats beyond any attempt to make him die, and continues to pulsate, for better or for worse, in black and white. What remains, in this ballet, of its first edition? Once the story has been reduced to the essential, and the accessory characters have been eliminated, Pimpinella, the young girl loved by Pulcinella, the Wizard, who uses light as a guide to find a way out in the course of history, and the two couples of lovers remain. The choreographer did not want to follow the plot built in 1920, but focuses on the personality of the protagonist and the main events that revolve around him: his love for Pimpinella, the alleged death, the ending, a symbol of rebirth.

“The final scene – says Merola – in which Punchinello once again wears his hat, which he often has inside the show, but which he often takes off to be similar to the rest of society, symbolizes his choice: he realizes that being as society would like takes him nowhere, and then chooses to be himself, chooses the truth.”